The truth, however, is far stranger. The woman called Guglielma was real enough, but even in her lifetime, she was already one of those mysterious, spellbinding figures whose destiny is to attract the powerful projections of others, for better and worse. Around 1260 she arrived in

Milanfrom parts unknown, apparently a widow, and adopted the life of a pinzochera--a religious woman living independently in her own home, much like the beguines of northern Europe. Her simple but charismatic teaching and her reputation as a healer quickly attracted disciples, both women and men, who clung to her and to one another with fierce loyalty. It was persistently rumored that she was a daughter of the King of Bohemia--a rumor that may have been true, and, whether it was or not, significantly enhanced Guglielma's claims to sanctity. By the time of her death on August 24, 1281, she was the center of a devoted religious famiglia. Buried in the Cistercian abbey of Chiaravalle, she immediately became the object of a saint cult with all the usual trappings. But canonization was not to be Guglielma's fate, for the ambitions of her inner circle extended far beyond it. Inspired by a man she called her "firstborn son," the layman Andrea Saramita, and a nun of the Umiliate order, Sister Maifreda da Pirovano, more than three dozen mostly upper-class citizens of Milan had come to believe that Guglielma was no less than the Holy Spirit herself, incarnate in the form of a woman. Despite her own vigorous denials, these devotees taught that the Holy Spirit had come to found a new, inclusive church, superseding the corrupt one ruled by Boniface VIII, and through her, Jews, pagans, and Saracens would be saved. After Guglielma's resurrection and ascension, this utopian church would be led by her "earthly vicar"--none other than Sister Maifreda, the papessa of the age to come. (6)

All this is heady stuff and, needless to say, heresy. Two decades after Guglielma's death, the activities of her apostles came, inevitably, to the attention of a Dominican tribunal charged with conducting inquisitions in Milan. In a lengthy trial extending from July through December of 1300, the year of jubilee, these inquisitors interrogated at least thirty-three citizens, including Saramita and Maifreda, both of whom paid for their doctrine with their lives. (7) A second nun, Sister Giacoma dei Bassani da Nova, was also burned at the stake, while many others were sentenced to wear penitential crosses and pay hefty fines. Guglielma herself was posthumously condemned on the basis of a confession almost certainly extracted by torture from Saramita. The Dominicans were less interested in ascertaining her genuine beliefs than in expunging her cult, which they could do only by exhuming her body--a desecration that would have been unlawful were she not a proven heretic. Having created the evidence they required, the inquisitors proceeded to have Guglielma's tomb dismantled, her images destroyed, her disciples' writings consigned to the fire, her bones burned and their ashes scattered, her memory utterly damned.

Nevertheless, a hundred and fifty years after these tragic events, someone in the obscure church of Brunate, where no inquisitor ever thought to go, took the trouble to commission a painting of this very saint, or rather, condemned heretic. As we shall see, the extant painting once accompanied an entire cycle of scenes from St. Guglielma's legend. But the painting that survives was preserved for a reason. It has for centuries been the object of veneration, and unlike the lost narrative cycle, it refers directly to the heretical beliefs of the thirteenth-century sect. For I believe we can identify the persons kneeling before St. Guglielma as none other than the ill-fated Sister Maifreda and Andrea Saramita. These are not random devotees, nor does Guglielma's fifteenth-century legend include any episode in which a nun and a bourgeois layman kneel to receive the saint's blessing. Rather, the clothing of these two figures marks them as precisely those disciples who were most deeply involved in spreading the doctrine of Guglielma's divinity. The figure of the saint herself, dressed in purple damask befitting her royal status, was until recently decked with a golden coronet above her wimple. (8) More tellingly, she wears three golden rings, two on her right hand which is raised in blessing, one on her left. The three rings, hardly a standard iconographic attribute, probably symbolize Guglielma's special relationship to the Trinity: two on her right hand to signify Father and Son, one on her left to represent the Holy Spirit--and with this hand she consecrates her earthly vicar. (9) Behind Sister Maifreda, who kneels in prayer, Saramita with his arms piously crossed over his breast awaits a blessing. (10) Although the faces have likely been retouched over the centuries, they have a portrait-like specificity: Guglielma's expression is stern to the point of fierceness. Behind her, the upper half of the panel is filled by a banner or tapestry of deep blue and gold brocade, whose ermine-lined borders again denote royalty. A scroll unfurled across this banner leaves room for a lengthy inscription that, alas, has long been illegible. (11)

The mystery of how the heretic of Milan became the saint of Brunate, once solved, throws a sharp light on the relationship between official and unofficial religion. Like the more celebrated history of Joan of Arc, Guglielma's trajectory leads from fervent veneration in her lifetime through heretication and burning to vindication as the object of an approved saint cult, which in the twentieth century extended even to the publication of indulgenced prayers. Although Guglielma's story is less spectacular than Joan's, it is still more irregular, since in her case no formal act of rehabilitation, much less canonization, intervened between the trial of 1300 and the fifteenth-century renewal of her cult. Instead, what we find is an unlikely convergence of popular piety, dynastic pride, female solidarity, and theatrical performance, winning a small but remarkable triumph over the forces of repression. Since a key factor in Guglielma's return to grace turns out to have been a play, I will present the vicissitudes of her life, death, and afterlife as a tragicomedy in five acts.

ACT ONE: A BOHEMIAN PRINCESS IN MILAN?

TO begin with the setting, Milan in the mid-thirteenth century was a hotbed of religious discontent. On April 6, 1252 a Dominican inquisitor,

Peter of Verona, was on his way back to Milan after celebrating Easter in Como when he was ambushed and murdered--not by the Cathars he was prosecuting, but by leading Milanese citizens who resented the inquisitors' prominence in civic life. Only a year later he was canonized as "St. Peter Martyr." (12) His enormous marble sarcophagus--a masterpiece of fourteenth-century sculpture--still dominates the Portinari Chapel at the ancient church of Sant' Eustorgio, where the Dominicans held their trials. From that point onward at least one inquisitor was always stationed there, while a group of eight controlled the office of inquisition for all Lombardy. (13) The Franciscans, usually at odds with their rival order, also had friars and tertiaries in Milan, and the predominantly female order of Umiliate had several houses, the most important being the convent of Santa Caterina di Biassono, where Sister Maifreda lived. (14) This order had come some distance from its radical origins to attain upper-class respectability--a familiar story in women's monasticism. Devout single women who did not wish to take vows as nuns or tertiaries could embrace the apostolic life as pinzochere, a more independent and therefore suspect option that did not require alliance with a particular order. Beyond the city walls to the southeast lay the great abbey of

Chiaravalle, named after Clairvaux and founded by St. Bernard in 1135. (15) Despite the primitive Cistercian mystique of "wilderness," Chiaravalle was very much an urban institution, the center of a group of religiously active laity who attended festivals and sermons there. Many of these, including Guglielma and some of her friends, entered into contracts of vitalizio with the abbey--a form of spiritual life insurance whereby they bequeathed their property to the monks in return for support as long as they lived, inclusion in the monastic community of prayer, and burial at the abbey with commemorative masses. (16)

The secular clergy and laity stood under the jurisdiction of their archbishop, who as of 1262 was

Ottone Visconti. But the Visconti, whose rise to power was just beginning, were bitter rivals of the Della Torre family, which ruled Milan at that point and refused to let the new bishop enter his city until 1277, when he finally did so by force of arms. In the meantime Milan lay under interdict, deprived of the sacraments. (17) In this context of civil and religious strife, it is not surprising that heresy had a certain appeal, especially when it offered some way beyond a patently corrupt institutional church. In particular, the prophetic ideas of the ex-Cistercian Joachim of Fiore (d. 1202) were embraced by the more radical branch of the Franciscan order, the so-called Spirituals, as well as some of the common people. Joachim, whose teachings were not condemned during his lifetime, had prophesied the advent of a Third Age or status of the Holy Spirit, superseding the ages of God the Father (the Old Testament era) and God the Son (from the Incarnation through his own days). Following an elaborate system of biblical typology, Joachim had predicted that the new age would begin in 1260, heralding the inauguration of an ecclesia spiritualis in which grace, spiritual knowledge, and contemplative gifts would be diffused to all. (18) Coincidentally or not, it was around 1260 that Guglielma, escorted by a grown son, appeared in Milan.

But whence? Maddeningly, we do not know and are not likely to find out. Since the inquisitors burned her followers' original writings, the only surviving primary source is the trial record (Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana A.227), which is itself incomplete but includes four official notebooks filled with interrogations and depositions. (19) Only a small number of the Dominicans' questions pertained to Guglielma's life and teachings; the majority concerned beliefs and practices of her devotees. Their first question to Saramita, however, was whether he had known Guglielma in her lifetime. When he acknowledged that he had, they asked "if he knew or had heard where this Guglielma was from. He answered yes, she was a daughter of the late king of Bohemia, as it was said. Asked if he had sought out the truth concerning this, he answered yes: he, Andrea, had gone to the king of Bohemia and found the king dead, and found that it was so." (20) This cryptic testimony was confirmed by a secular priest, Mirano da Garbagnate, who had accompanied Saramita on his journey from Milan to Prague. (21) In February 1302, long after the burning of Guglielma's bones, the lay brother Marchisio Secco testified in the mopping-up phase of the trial that she "had been a woman of good birth, and it was said that she was a sister of the king of Bohemia." (22)

The kings in question would have been Premysl Otakar I (regn. 1198-1230), Guglielma's father, and his son and heir, Wenceslas or Vaclav I (regn. 1230-1253). Wenceslas in turn was succeeded by his son Premysl Otakar II, who was killed in battle in 1278, leaving a child as heir. A disastrous interregnum followed his defeat, and the throne remained vacant until 1283. (23) Andrea Saramita must have visited Prague in the spring or summer of 1282, since we know he was still in Milan for the solemn translation of Guglielma's body in October 1281. During his sojourn in Bohemia, then, he would indeed have "found the king dead." Now it is most unlikely that a citizen of Milan, testifying in 1300, would have known or cared that there had been a Bohemian interregnum exactly eighteen years earlier unless he had actually been there; nor would he have made such a difficult and expensive journey without good reason. That reason, as it later emerged, was to notify the royal family of Guglielma's death in order to obtain support for her canonization. Saramita's hopes were not unfounded, for the royal houses of Bohemia, Hungary, and Poland were famous for nurturing saintly princesses. If Guglielma was a daughter of Premysl Otakar I by his second wife, Queen Constance of Hungary, then she was also a first cousin of St. Elizabeth of Hungary (d. 1231); a half-sister of Margarete (d. 1212/13), who married

King Waldemar II of Denmark and was revered as a saint in that land; and a full sister of St. Agnes of Prague (d. 1282), a Franciscan abbess whose canonization was first proposed in 1328, though not achieved until 1989. (24)

The only problem with this scenario is the absence of any corroborating Bohemian documents. Baptismal records, which were seldom preserved even by royalty, are lacking for Guglielma's siblings as well; but it is more unusual to have no documentation of a princess's marriage. One possible explanation is that Guglielma's devotees invented her royal descent to shore up their hagiographic claims. But another, more likely in view of Saramita's visit to Prague, is that she could have been illegitimate. (25) After all, Premysl Otakar's first marriage was clandestine and his second was bigamous: when the pope refused to dissolve his irregular union with Adele of Meissen after he tired of her, he simply disinherited Adele and her children and took a new queen. (26) It would be unsurprising if a king with so little regard for canon law had begotten a few bastards.

Whatever her origins, Guglielma did marry--unless she herself had an illegitimate child, which seems unlikely in view of the austere evangelical life she led in Milan. If she had married an Italian nobleman, she would have learned the language and perhaps moved to Milan in widowhood because of its nearness to her marital home. On the other hand, an early tradition locates her origins in England. The Annals of Colmar for 1301 state that "in the preceding year there came from England a very beautiful virgin, as eloquent as she was fair, saying that she was the Holy Spirit incarnate for the redemption of women; and she baptized women in the name of the Father and of the Son and of herself. After death she was brought to Milan and burned there." (27) A fifteenth-century legend of St. Guglielma, as we shall see, makes her a daughter of the English king and wife of the king of Hungary, although this hagiographic romance could have been influenced by the popular legend of St. Ursula, supposedly a British princess. Nevertheless, we know that Premysl Otakar I negotiated with the English king Henry III about a possible marriage alliance between Henry and Agnes in 1227, and this embassy could have provided an occasion for Guglielma's marriage to some English lord. (28) It was perhaps on the occasion of her marriage that she changed her name, for as she told her followers, it had originally been Felix (that is, Italian Felice or Czech Blazena). (29)

Most historians estimate the year of Guglielma's birth as circa 1210. As for the day, she herself said she had been born on Pentecost, doubtless fueling theological fantasies. (30) At any rate, she must have been a mature woman of about fifty when she came to Milan, where she lived for some twenty years. Her life in that city is only slightly better documented than her mysterious youth. Saramita would later tell the inquisitors that Guglielma led a "common life," that is, she avoided idiosyncrasies in food and dress, wearing a simple brown habit that they too adopted. (31) In 1274, acting as lay procurator for Chiaravalle, he bought a house for her in the neighborhood of

Porta Nuova, and it was there that she spent the final years of her life. (32) Nothing in the little we know of her teaching explains the intense fascination that she exerted on those around her. She warned merchants to avoid usury and fraud, as any religious person might have done; comforted the sorrowful; prayed for the sick and was credited with healings; and on her deathbed, encouraged her devotees to remain together as a famiglia, showing each other love and respect. (33) Many of them did belong to a small group of closely linked families. Saramita's mother, sister, and daughter were all members of the inner circle, which also included the physician Giacomo da Ferno and his son Beltramo; the widow Sibilla Malconzato and her son Franceschino; Bellacara Carentano, her son, three daughters, and her maid; the brothers Ottorino and Francesco da Garbagnate; a married couple, Stefano and Adelina Crimella; and two sisters-in-law, Pietra and Catella degli Oldegardi. Most of these people were affluent and several belonged to Milan's ruling class; yet a poor, unmarried seamstress named Taria was one of the sect's most committed members, selected (despite objections from the social elite) to be a cardinal in the church to come. (34) Even more strikingly, the Carentano family generally supported the Della Torre faction, while the Garbagnate were staunch allies of the Visconti. (35)

Here we see one index of Guglielma's powerfully charismatic personality: she was able to persuade these natural enemies not only to tolerate each other during her lifetime, but to maintain intimate friendships in her name long after her passing. This ability to command deep loyalty from her disciples, but what is more, to forge profound and lasting bonds among them, must surely have been one of the traits that reminded them so vividly of Jesus. In an age aflame with the ideal of the "apostolic" or "evangelical" life, Guglielma came to embody her followers' desire, not only for a living saint, but for a visible, palpable witness to the Incarnation. Like St. Francis she was believed to bear the stigmata, although only one disciple (Adelina Crimella) said she had actually seen and touched them. (36) Like Francis too, as well as countless female mystics, she understood her mission as a sharing in Christ's Passion through the power of the Holy Spirit. Decades later, Francesco da Garbagnate still remembered her enigmatic claim that "from the year 1262 onward"--the year of the interdict--"the body of Christ had not been sacrificed or consecrated alone, but along with the body of the Holy Spirit, which was Guglielma herself." (37) Whatever she may have meant by this saying, some of her disciples came to interpret it in a very literal sense.

Rumors of divinity already swirled around Guglielma during her lifetime. Her words about "the body of the Holy Spirit," together with her mysterious royal origins, Pentecostal birth, imputed healings, and stigmata, coalesced to create a more-than-human mystique in the minds of her friends, especially Saramita, who interpreted these data in the light of Joachite expectations about the coming age of the Spirit. As early as 1276, according to Allegranza Perusio, she first heard from Saramita that "Guglielma was the Holy Spirit and the true God." Her response was to go to Guglielma herself and ask if this was the case, but "Guglielma replied to the witness that she took this as evil; she was a lowly woman and a vile worm." (38) When asked to perform healings, as Sister Maifreda testified, Guglielma would tell miracle-seekers, "Go away! I am not Cod." (39) The nobleman ser Danisio Cotta said that around 1278 or perhaps earlier, he had heard from a certain Carmeo da Crema--deceased before the trial--"that through Guglielma, the Jews and Saracens should come to faith and salvation." But he had also heard Guglielma repudiate such claims in Saramita's presence: "You are fools! What you say and believe about me is not so. I was born of a man and a woman." (40) On yet another occasion, Saramita made a wager with Marchisio Secco, a lay brother at Chiaravalle, that Guglielma was the incarnation of the Spirit. They asked her to settle this bet, and she "very angrily, as it seemed, replied to them that she was flesh and bones and had even brought a son into the city of Milan; and she was not what they believed; and unless they did penance for those words they had said about her, they would go to hell." (41) But Saramita by this time was so convinced of his belief that he preferred inquisitorial fires, if not hellfire, to the disappointment of his hopes.

ACT TWO: A CULT WITHIN A CULT

When Guglielma died in the late summer of 1281, troop maneuvers in a war between Milan and Lodi prevented her immediate burial at Chiaravalle, to which she was entitled by virtue of her vitalizio arrangement with the abbey. Hence she was initially buried at her parish church of San Pietro all'Orto and translated two months later, with a safe-conduct for her escort from the Milanese field commander. (42) From the outset, however, the skirmishing over Guglielma's body revealed both a convergence and a potential competition between two incipient cults: the public saint cult that would eventually draw a wide swath of citizens to her shrine and the private, esoteric cult that would draw the wrath of the inquisitors. Somewhere between the two lay the abortive canonization effort that led Saramita and his colleague to Bohemia. (43) Guglielma's devotees spent a large outlay of private funds on altar frontals, liturgical vessels, and elaborate vestments connected with her cult, but the record reveals an interesting disagreement as to the purpose of these goods. Some believed they were meant for her canonization Mass or the translation of her body to Prague, while others thought they were to be kept in readiness for her resurrection from the dead or for the solemn Mass that Sister Maifreda would celebrate as papessa in Santa Maria Maggiore. (44) Even the original sarcophagus in which Guglielma was buried became a contested relic at the time of her translation. San Pietro all'Orto wanted to retain it to have a share in the anticipated saint cult; but the monks of Chiaravalle, wishing to prevent competition, arranged for it to be kept instead in the private home of a devotee. (45) There--without the knowledge of either church--it doubtless served the purposes of the esoteric cult.

Chiaravalle quickly became the center of Guglielma's public veneration. Pilgrims visited her tomb and lighted candles before her image, while the abbot appointed Marchisio Secco to tend the lamps there and keep a record of miracles. Twice a year on the anniversaries of her death (August 24) and translation (around All Saints' Day), the monks celebrated her office publicly and preached to a lay audience in her honor. The record mentions one such sermon by Marchisio da Veddano that attracted an audience of "over 129 persons, both men and women." (46) After the service the abbot would invite the devotees to an evangelical feast of bread, wine, and chickpeas. (47) Yet, oddly enough, not a single monk was called to testify in the inquisition of 1300, at least not in the portion of the transcript that comes down to us. What is more, Marchisio da Veddano, the monk whose name appears most frequently as an avid proponent of Guglielma's cult, became abbot in 1303, only three years after the trial. (48) So either the abbot of Chiaravalle, who managed to disrupt the proceedings for a time with a challenge to the inquisitors' legal authority, (49) was able to pull strings behind the scenes to protect his community; or else the monks were genuinely unaware of the heretical devotions in their midst. Or perhaps both, for the two possibilities are not mutually exclusive.

If Chiaravalle was the public cult center, the convent of Umiliate nuns at Biassono was the epicenter of Guglielma's private cult. There Sister Maifreda held undisputed sway, performing audacious priestly actions that included anointing devotees with the holy water in which Guglielma's relics had been washed; blessing and distributing hosts that had been consecrated at her tomb; preaching to her sisters and lay devotees about the Gospel and the saints; and ultimately celebrating Mass, although that climactic event did not take place until Easter 1300, three years after she had been asked to leave the convent for its security. (50) Several devotees honored Sister Maifreda as the Holy Spirit's earthly vicar by kissing her hands and feet and addressing her as "Lord Vicar" or "Lady by the grace of God." (51) Unlike the monks of Chiaravalle, the nuns of Biassono were fully aware of St. Guglielma's esoteric role, for an altarpiece at the convent showed the Trinity with Guglielma as the third person, delivering captives from prison--an allusion to the Harrowing of Hell, with Jews and Saracens to be saved by the Holy Spirit as Christians were by Christ. (52) On St. Catherine's day--the patronal feast of the community--laywomen gathered with the nuns at Biassono for a special festive meal, and Sister Maifreda sometimes preached about Guglielma on these occasions under the guise of St. Catherine. That saint also served as an iconographic cover for Guglielma. The sectarian Mirano da Garbagnate, a painter before he was ordained priest, confessed to painting Guglielma under the name of St. Catherine in the churches of Sant' Eufemia, Santa Maria Minore, "and elsewhere in many places." (53) Sacred images were particularly valued by Guglielma's devotees; Danisio Cotta had an icon of her painted over his brother's tomb at Santa Maria fuori Porta Nuova. (54) Although the inquisitors would have destroyed these public images of St. Guglielma after the trial, it is possible that others survived in domestic chapels--a point to which we shall return.

In addition to the cult activities at the two monasteries, members of the sect met frequently for meals and devotions in each other's homes. To the two feast days of St. Guglielma observed at Chiaravalle, they privately added a third on Pentecost. (55) Calling themselves "the children of the Holy Spirit," they had their own personal cultic roles: Saramita was Guglielma's "only-begotten" or "firstborn son," Maifreda her earthly vicar, Mirano da Garbagnate their "special secretary," and Taria Pontario a cardinal-elect. (56) Like the apostles after the death of Jesus, Guglielma's faithful received spiritual guidance through visions, and it was to these posthumous encounters with her that they ascribed the authority of their teaching. The movement's theology took a typological form inspired by Joachite ideas: just as the New Testament had superseded the Old, devotees set about composing their own epistles, gospels, and prophecies that would eventually supersede the New. Their considerable literary production also included a vita, hymns, litanies, and vernacular canzoni addressed to the Holy Spirit. (57) But Guglielma herself was not so much a successor to Christ as his exact feminine counterpart: like Christ she was expected to rise from the dead, ascend into heaven, send the Spirit upon her disciples, and found a new church through the agency of the papessa. It followed that the present, corrupt Church had no spiritual authority, nor did its pope, who at the time of the trial was the widely detested Boniface VIII.

These beliefs are set forth in tidy propositional form in the trial record, where the devotees generally respond "yes" or "no" to a standardized set of questions; but it does not follow that they would have chosen such forms of expression on their own. G. G. Merlo and Marina Benedetti have spoken aptly of the devotees' "spiritual dreams" being crystallized into formal heresy through the filter of these interrogatories. (58) In their private conversations and musings, Guglielma's friends probably held a range of views about her, views at least as diverse as the Christologies of the New Testament. But certain tenets and practices appear to have been shared by all: a reverence for Guglielma as a uniquely Spirit-filled person, even a physical embodiment of the Spirit; an interest in gender complementarity; a belief in the priestly capabilities of women; an inclusive ecclesiology embracing the ultimate salvation of Jews, Saracens, and pagans; a fascination with such "charismatic" phenomena as visions and prophecies; and vivid hopes for a utopian future. Saramita, the theologian of the sect, clearly played the largest role in shaping these views, while Sister Maifreda embodied them in concrete liturgical practices. (59)

Seen in their historical context, the Guglielmites may stand closest to the persecuted Spiritual Franciscans and their lay affiliates, the beguines of southern France, who shared with them an attraction to Joachite prophecy. The Provengal heresiarch Na Prous Boneta, burned in 1328, would develop a conception of her own role as donatrix of the Holy Spirit for the coming age, not unlike the role that Saramita and Sister Maifreda had ascribed to Guglielma. (60) From a broader theological perspective, the little band of

Milanese devotees anticipate the mid-nineteenth-century Shakers, who like them believed that the Godhead must be incarnate in both masculine and feminine forms for the salvation of all. (61) The Shakers, however, would insist on celibacy, separation from the world, and a highly ascetic lifestyle, whereas the "children of the Holy Spirit," so far as we know, remained contentedly in the mainstream of Milan's social and liturgical life.

ACT THREE: THE INQUISITIONS OF 1300 AND 1322

The trial of 1300 was not the first time Guglielma's followers had received unwelcome attention from a Dominican tribunal. In 1284, only three years after her death, an inquisitor tipped off by an informer had interrogated Saramita, Sister Maifreda, and Sister Giacoma dei Bassani da Nova, among others. All of them escaped with symbolic punishment and a warning after repudiating their errors. Because of this prior inquisition, it was these three who stood in mortal danger in 1300, ultimately facing death as relapsed heretics. (62) In August 1296, as Guglielma's cult continued to flourish despite the friars' disapproval, the newly elected Boniface VIII issued the antiheretical bull Saepe sanctam Ecclesiam, authorizing action against laypersons, "even of the female sex," who usurped priestly authority by hearing confessions, forming conventicles, preaching, and bestowing the Holy Spirit through the imposition of hands. (63) It was at this perilous moment that the inquisitor Tommaso da Como initiated new proceedings against Guglielma's devotees. The first and only person to be questioned this time was Fra Gerardo da Novazzano, a tertiary heavily involved in the sect, who would try (successfully) to escape the death penalty for relapsi in 1300 by turning informer. But the initial action against him went no further because of a procedural glitch: a man named Pagano da Pietrasanta, the defendant in a concurrent Milanese trial, appealed unexpectedly to the pope. His appeal was accepted, that trial was removed to the curia, and Fra Tommaso da Como was suspended from his duties and recalled to Rome. (64)

During the four-year hiatus that followed, it would be an understatement to say that the Milanese did not lament the inquisitors' absence. By the time they returned in the summer of 1300, both the local Franciscans and the abbot of Chiaravalle had inferred that the Dominicans no longer held papal authority to conduct inquisitions in Milan. (65) The tribunal's renewed action against Guglielma's followers may have been particularly resented because so many belonged to prominent upper-class families, but also because even those outside the inner circle were devoted to their saint and did not want to see her reputation tarnished. Finally and most crucially, Sister Maifreda da Pirovano happened to be a first cousin of Matteo Visconti, who since 1287 had been Captain General and by 1300 was lord of Milan. Since the Visconti belonged to the Ghibelline or pro-imperial party--as opposed to their Guelph or papalist rivals, the Della Torre--the Guglielmite trial took place in a climate of marked hostility between the inquisitors and the ruling family. To be sure, Matteo Visconti in 1300 appeared to be at the apogee of his power. It was in that very year that he threw a splendid wedding for his eldest son, Galeazzo, who married Beatrice d'Este, sister of the Marquis of Ferrara. Matteo then named Galeazzo as sharer in and presumptive heir to his lordship. (66) But a condemnation of their close relative, Maifreda, for heresy could have been worse than embarrassing to the family's dynastic hopes--especially since, as we learn from later documents, Galeazzo himself was rumored to be

an initiate in the heretical sect.

At this point we cannot fully understand either the events of 1300 or the subsequent revival of Guglielma's cult without considering a second heresy trial, that of the Visconti themselves, in 1322. The political context of this trial was the long-standing struggle between Guelphs and Ghibellines for control over the cities of Lombardy. In the wake of Sister Maifreda's condemnation, the exiled Della Torre had staged a comeback in Milan and returned to power in 1302. Matteo Visconti judged it prudent to withdraw to Verona for a time, while Galeazzo retreated to his wife's family seat in Ferrara. But the interval of Della Torre hegemony ended after that family disastrously split its own loyalties between two rival heads, the Captain of the People and the Archbishop. During this feud it chanced that the new emperor,

Henry VII, came to Milan for his coronation and found himself warmly, if opportunistically, welcomed by Matteo Visconti. (The diplomatic groundwork for Henry's visit had been laid by Matteo's close friend, Francesco da Garbagnate, whom we have already met as one of Guglielma's most ardent devotees.) During the emperor's stay in Milan, the Della Torre made the mistake of spearheading an unsuccessful plot against him, which resulted in the family's lasting disgrace and exile. (67) But Henry VII rewarded Matteo's loyalty by creating him Imperial Vicar of Milan in 1311, and Matteo celebrated his return to power by expelling the hated papal inquisitors from the city.

In the unending struggle of Guelph and Ghibelline, however, no triumph was ever final. The restored Matteo Visconti embarked on a policy of territorial aggression so relentless that Pope John XXII, taking advantage of Henry's death in 1317, deprived Matteo of his imperial title, reassigned it to one of his Guelph allies, and summoned Matteo to the curia at Avignon to answer a series of charges. Matteo refused, incurring excommunication and giving further cause of war. But the Visconti armies defeated the papal troops, so John XXII resorted to new spiritual weapons. In February 1321 he summoned Matteo to Avignon once more, this time to be tried by an inquisitorial court on charges of sorcery and heresy. The outcome was of course a foregone conclusion. On February 23, 1322, the pope placed Milan under interdict and declared a "crusade" against Matteo Visconti and his sons, promising a plenary indulgence to all who would take up arms against them, and a month later, the Visconti were again found guilty of contumacious heresy. (68)

The sorcery charges, though spectacular, were eventually dropped. On the testimony of a single witness--a disgruntled Della Torre partisan exiled from Milan for debt--Matteo and

Galeazzo Visconti were accused of invoking demons and practicing witchcraft against the pope with the aid of a necromancer. The chief, though specious, interest of this charge is that it fingered Dante as an accomplice in sorcery because the poet's patron, Can Grande Della Scala, was head of the Ghibelline League. But the heresy charges are, from our perspective, more important. Matteo was accused of denying the Resurrection, Galeazzo of denying that fornication is a sin, and both of violating nuns. In the midst of such accusations, we find detailed and plausible charges that both father and son were compromised by their involvement with "the heretic Maifreda" and her partisans. (69) Their association with the Guglielmites forms part of a larger pattern of anticlerical and anti-inquisitorial activities. Among other things, Matteo is accused of violently arresting and detaining clerics, interfering with the pope's messengers, "impeding the office of inquisition" in many places, (70) imprisoning the bishop of Vercelli, imposing unlawful taxes on churches, intruding unworthy persons as superiors of religious houses, disrupting a crusade sermon, and bribing Saracen kings to take arms against John XXII. Guilt by association figures prominently: Matteo's grandmother was allegedly defamed for heresy, as was his uncle Ottone, the late archbishop of Milan. Another witness claims that the heresiarch Fra Dolcino was on such intimate terms with Matteo Visconti that Dolcino raised an army at his command.

As for his relationship with Sister Maifreda, an informant testifies that "during the trial against Maifreda and her heresy, many things would have been said and discovered against the faith if they had not been dismissed for fear of

Matteo, who then ruled Milan; they were not disclosed because those who knew of them did not dare reveal them for fear of Matteo." (71) Another witness declares on the basis of hearsay that Matteo petitioned for the release of several persons defamed for heresy during this trial, including one Guido Stanfeo. According to another charge, he "petitioned for the liberation of the heretic Maifreda when she had already been arrested and handed over to secular judgment." Finally, during his lordship Matteo promoted and took as counselors men who were well known for heresy. Among these were "Francesco da Garbagnate, who belonged to the sect of Maifreda and was signed with the cross for this; ... also Andrea [Saramita], the burned heretic; Albertone da Novate, Ottorino da Garbagnate, Felicino Carentano, Franceschino Malconzato, all signed with the cross." (72) An Augustinian lay brother called Fra Pezzolo claimed that Galeazzo, who would have been quite young in the movement's heyday, "belonged to the sect of Maifreda the heretic" and served as her doorkeeper. On the testimony of another witness, Galeazzo would have been signed with the cross in 1300--that is, made to wear the yellow crosses of a heretic on his clothes as a badge of shame--"if his father Matteo had not made him go to the inquisitor's feet with laces around his neck so he would spare him." (73)

How credible are these charges? Given the clearly political motivation of the trial and the anonymity of most witnesses, much could have been invented from sheer malice. We will never know if Matteo Visconti really tried to kill Pope John XXII by fumigating a silver statue inscribed with the name of a demon, or if

Galeazzo "put the body of Christ in a frying pan with hot water so that the devil would keep him in power." (74) Charges that the signori raped nuns, defended fornication, and denied central Christian doctrines could have been fabricated merely to discredit them. On the other hand, the anticlerical and antipapal activities cited by witnesses clearly fit the family's political agenda, and many would have been matters of public knowledge. The charges pertaining to the Guglielmites lie in a gray area, but there is nothing inherently implausible in them, and some interesting circumstantial evidence adds to their credibility.

First among these suspect circumstances is the very survival of the record. The archives of the Milanese inquisition were destroyed in 1788, leaving only the proceedings against the Guglielmites as testimony to that tribunal's activities. The manuscript that interests us survived only because it had long since disappeared from the Dominican archives, and its provenance is very strange indeed. According to Michele Caffi, the historian of Chiaravalle, the Guglielmites' trial record was discovered by Matteo Valerio, the Carthusian prior of Pavia (d. 1645), "in a grocer's shop." After studying the manuscript Valerio gave it to the historian Giovanni Puricelli, whose heirs bequeathed it with his other manuscripts in 1676 to the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, where it remains to this day. (75) It seems that it had already gone missing by the time the Milanese humanist Bernardino Corio (d. 1519) wrote his Storia di Milano, for his account of the Guglielmites is based entirely on stock antiheretical cliches and shows no awareness of the movement's true nature. (76) Even as early as the 1420s, Guglielma's saint cult was being revived in ways that would have been most unlikely if the record of her condemnation had still been at hand.

The likeliest explanation of the manuscript's disappearance, I believe, is that Matteo Visconti confiscated it from the Dominicans around 1317, when he "violently expelled from Milan four inquisitors of heretics called by the authority of the Lord Pope." (77) If the document incriminated not only his cousin Maifreda, but also his son Galeazzo, his friend Francesco da Garbagnate, and several of his trusted counselors, he would have had good reason to do so. (78) To be sure, there is an alternative possibility: John XXII's agents could have taken the manuscript to Avignon to help them construct their case against the Visconti. But this seems unlikely because, had they done so, it would have remained in an official archive in Avignon or Rome. Moreover, it appears that the document may have been expurgated to remove its most incriminating portions. Granted that all the records of one of the two principal notaries are lost, even the surviving record must be an altered copy rather than the original transcript, for all the depositions it contains are dated yet do not appear in chronological order. (79) Most of the sentences are missing, including Guglielma's own condemnation and the death sentences of Saramita and Sister Maifreda, although that of Sister Giacoma da Nova remains. We learn of Saramita's death indirectly from the interrogation of his widow about his property, but we know of Sister Maifreda's execution only through the Visconti trial records of 1322. Curiously, no sentences are extant for any of Matteo Visconti's associates named in the record of 1322 as crucesignati--Albertone da Novate, Francesco and Ottorino da Garbagnate, Felicino Carentano, and Franceschino Malconzato--although we do have records of the same penalty meted out to seven others. Galeazzo Visconti is not mentioned in the extant manuscript at all, while Guido Stanfeo--the other person whose release Matteo is supposed to have demanded--is named only as a member of the judiciary panel convoked by the archbishop of Milan to ratify the sentence of Sister Giacoma da Nova. (80) Finally, Albertone da Novate, one of the highest-ranking members of the sect, is named prominently in all the deponents' lists of people who participated in their activities; but either he was never asked to testify (although his mother was), or else his testimony is lost. Yet we have evidence that he was still living in Milan during the trial, since he told friends about a vision in which he saw St. Guglielma and an angel liberating Saramita and Sister Maifreda from the inquisitors' clutches. (81)

Like all arguments from silence, this one remains on the level of speculation but seems to fit the evidence better than any alternative theory. For example, it would explain why the manuscript was eventually found in Pavia, for that is the place where the vast Visconti-Sforza library was housed before it was pillaged and dispersed in the sixteenth century, after the fall of the dynasty. (82) My theory does raise a perplexing question, however: If Matteo Visconti saw fit to confiscate the trial record as soon as he had the opportunity, why did he not simply destroy it, rather than preserving a bowdlerized version? The answer, I suggest, is that in spite of the inquisition, the Visconti continued to cherish the memory of St. Guglielma and Sister Maifreda, and were determined to preserve a record of their religious movement in private hands where the knowledge could do no further harm. While it may be hard to see much affinity between the hardboiled lords of Milan and the "children of the Holy Spirit," those utopian dreamers, who had no political plan beyond divine intervention to set Maifreda on the throne of Peter, we know that violence and piety were no strangers to one another in the medieval world. In this case, dynastic pride proved to be as strong and determined a force as inquisitorial zeal, for nothing can explain the astonishing resurrection of Guglielma's cult in the fifteenth century except the resilience of Visconti patronage over the long haul.

ACT FOUR: THE REINVENTION OF ST. GUGLIELMA

After a century of silence, St. Guglielma suddenly reemerges from the shadows around 1425, with a full-length hagiographic vita that bears only the faintest resemblance to her actual story. Her latter-day legend was the work of Antonio Bonfadini, a friar of Ferrara (d. 1428), as we learn from a contemporary's list of Franciscan writers. (83) Nothing is known of this author except that he also produced a collection of sermons and one other vernacular saint's life. But the very existence of the legend reveals that St. Guglielma's popular cult had not only survived the inquisition of 1300, but spread well beyond the confines of Milan. There is no way to know how widely she was venerated outside of her adopted city before 1300. If her cult had already spread to neighboring cities and villages, carried by Milanese travelers, it is possible that devotees outside of Milan remained either unaware of or undeterred by her posthumous heretication. But the reemergence of her sainthood in Ferrara is not totally surprising, for it is to that city that

Galeazzo Visconti withdrew to join his wife's family during the

Della Torre ascendancy of 1302-10. It would have been an act of piety and defiance alike if, to spite the inquisitors, he had brought the devotion to St. Guglielma with him. In any case, Bonfadini's text presupposes the prior existence of a cult without a vita. Somewhere in Ferrara a saint named Guglielma was being worshipped, perhaps even in a chapel dedicated to her name; but by 1425, no one remembered who she was. So the path lay open to invention.

Bonfadini's work may be his free literary creation, or it may incorporate tales already attached to the saint in popular legend. The story he tells is a version of the Calumniated Wife, one of late medieval Europe's best-loved folktales. Chaucer's Man of Law's Tale is a distant analogue. The story of Patient Griselda is related at a further remove, though it is a tale Bonfadini is more likely to have known through the versions of Petrarch and Boccaccio. Whatever his sources, the friar presents St. Guglielma as a daughter of the king of England, sought in marriage by the newly converted king of Hungary. The pious maid would have preferred to remain a virgin but consents in obedience to her parents. Once married, Guglielma "preaches so assiduously" to her new husband that he begins to delight in the stories of saints and the Passion of Christ. So she proposes a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, but to her disappointment, the king decides to go alone and leave her behind as regent. No sooner has the king departed than his brother, who is supposed to be protecting the queen, begins to make lustful advances to her. When she rejects them, he sets his heart on vengeance, which he obtains by going to meet the king as he returns from Jerusalem. With feigned reluctance, he tells the king that the queen has betrayed him with a squire, as everyone in the palace knows. He then vows that he will never return to court until the treacherous queen is dead. Without waiting to learn more, the king regretfully condemns his wife to death by burning--a sentence to be carried out by night to avoid public scandal. Fortunately, however, Guglielma's heartfelt prayers persuade her executioners that she is innocent, so they free her and burn an animal instead, presenting its bones to the judges along with some scorched rags of the queen's vesture.

Guglielma meanwhile escapes into exile, dressed in squalid peasant garb. One day as she hides in a forest, waiting to continue her journey by night, she is surprised in a thicket by hunting dogs. The huntsmen, seeing a pretty but shabbily dressed young woman alone in the woods, assume she is sexually available. But Guglielma appeals against them to the lord of the hunt, who turns out to be the

king of France. With all her modesty and eloquence, she pleads with him to protect an honest poverella from abuse. Impressed by her courtly bearing, he decides she cannot possibly be a peasant and resolves to bring her home to his wife as a lady-in-waiting. Although the queen of France is initially put off by her vile clothing, she becomes deeply attached to Guglielma once she has seen her in court attire. In fact, when the queen bears her firstborn son shortly afterward, Guglielma is chosen to be his governess. All goes well until the seneschal, falling in love with Guglielma, asks for her hand in marriage. The king and queen are delighted with the proposed alliance, but Guglielma tactfully declines without acknowledging that she already has a husband. History now repeats itself, and the spurned seneschal, like the Hungarian king's brother, is bent on revenge.

An opportunity presents itself when the seneschal finds the young prince sleeping alone in Guglielma's chamber while she is at church. Quickly he strangles the boy and plants evidence pointing to Guglielma. The saint is thrown into prison, even though the king and queen cannot quite believe that she is guilty of so heinous a crime. "Rigorously examined," Guglielma swears she is innocent but cannot name the real murderer. The seneschal, however, stirs up the judges to cry for her death, saying she has bewitched the king and queen so they cannot believe in her guilt. Once again, however, God delivers Guglielma from persecution. The Virgin Mary appears to her in a dream, giving her the power to heal all sufferers who are truly repentant and willing to confess their sins. Then, on the night she is to be burned, two angels cause the executioners to fall asleep while Guglielma prays. As they slumber, the angels escort her to a castle by the sea, where they pay her passage aboard a mysterious ship. On the voyage Guglielma has occasion to display her gift of healing when all the sailors are suddenly afflicted with terrible headaches. After this they hold her in the greatest reverence. When the ship arrives at an unnamed shore, the captain escorts Guglielma to a nunnery where his aunt is abbess. The saint says she "is not disposed to become a professed nun," but happily agrees to remain with the sisters as their servant. To further inquiries about herself she replies only, "I call myself a great sinner; my people are those who wish to do the will of God." (84) During her three years at the convent as cook, portress, and lay sister, Guglielma continually heals those who come to her and develops a great reputation for miracles.

At last it happens that her Hungarian

brother-in-law, who had sent her to the stake through slander, is punished by God with

leprosy. By a strange coincidence the same fate befalls the seneschal of France. Both men repent of their secret sins and decide to go on pilgrimage to the famous healer, accompanied by their respective kings. Guglielma, learning of these imminent visits, disguises herself by putting on a nun's habit. She then entices her former enemies into making full confessions in the presence of the French and Hungarian kings, whom she has first bound by a promise to forgive the men no matter what they might reveal. In the presence of a large crowd, Guglielma makes the penitents kneel and cleanses the lepers. Finally she discloses her own identity and history, much to their astonishment. Returning home at last with her husband, she lives happily ever after, giving alms to the poor and establishing many churches and monasteries, until God calls her to everlasting bliss.

This hagiographic romance is a potpourri of motifs that, at first blush, have little to do with Guglielma of Milan but are more reminiscent of St. Ursula, Constance, Griselda, and even Guinevere. (85) There are nevertheless a few points of rapport with the historical Guglielma. The saint is said to be English, as in the 1301 Annals of Colmar, but her union with the Hungarian king recalls her East European origins. She is a victim of slander and unjust prosecution who--twice--narrowly escapes being burned at the stake, as her followers were. Though famed as a healer, she calls herself a sinful woman. Living much of her life in exile, she is deliberately mysterious about her native land. Finally, just as Guglielma of Milan made close friends at the convent of Biassono but never became a nun, the Guglielma of Bonfadini's legend spends several years at a nunnery but remains a laywoman. The friar does not specify the order or location of this convent: although his heroine moves from England to Hungary to France, her sojourn with the nuns is left so vague that she could be claimed by any that wanted her--and in the end, it was the convent at Brunate that did.

Bonfadini's vita did not circulate widely. In fact, it survives in a single manuscript, which remained with the Franciscans of Ferrara until the time of Napoleon. But either his text or one derived from it eventually reached a Florentine humanist, Antonia Pulci (1452-1501), whose version gave the tale far greater currency. Pulci was a playwright who wrote convent dramas; after her husband's death in 1487 she lived as a pinzochera in Florence, just as Guglielma herself had done two centuries earlier in Milan. The Play of Saint Guglielma, one of seven dramas in Pulci's canon, versifies Bonfadini's legend in rhyming eight-line stanzas broken up among the dramatis personae, and wisely simplifies its plot. (86) Omitting the episode at the French court, Pulci moves directly from Guglielma's first escape from the stake to her dream of the Virgin, sea voyage, and sojourn with the still unidentified nuns. She also modifies the end of the legend: the king of Hungary, Queen Guglielma, and her brother-in-law all resolve to leave the court and live as hermits, and since the king is childless, his barons are left to govern the realm as they see fit. Our unworldly playwright does not concern herself with the civil war that doubtless would have ensued. But in other respects her play remains faithful to Bonfadini's vita, and its publishing history shows that she knew what her public wanted. Aside from convent performances, thirteen editions of Saint Guglielma were printed in Florence between 1490 and 1597, in addition to three Sienese editions (1579, 1617, and one undated). Further seventeenth-century editions were published in Venice, Viterbo, Macerata, Perugia, and Pistoia, though--strangely enough--never Milan. (87) It would be safe to say, then, that Antonia Pulci's efforts kept St. Guglielma's fame alive throughout northern Italy until the end of the early modern period. But Pulci's drama represents only the exoteric revival of Guglielma's cult. For the esoteric side we must turn again to the Visconti, and to two very different women.

Guglielma's heretication had tarnished the career of Milan's first lord, Matteo Visconti, but in compensation her sanctity would brighten the life of the last Visconti, Duchess

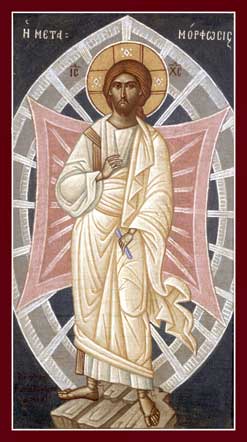

Bianca Maria(1424-68). The last duke of the male line, Filippo Maria, married twice but had no legitimate issue; Bianca Maria was his sole surviving child by his mistress, Agnese del Maino. At the age of eight, she was betrothed to the military captain Francesco Sforza, whom she married at Cremona in 1441, despite the fact that Filippo Maria had changed his mind in the interim and refused to attend the wedding. (88) Nevertheless, the marriage turned out well. Bianca Maria proved both pious and fertile, bearing eight children and founding numerous churches, and won unanimously warm commendations from the chroniclers of her time. (89) Portraits of the couple by the bride's favorite painter, Bonifacio Bembo, can still be seen in Milan's Pinacoteca di Brera. (90) The same artist also received another, less public commission to celebrate the union of the great condottiere with the ducal house: sometime between 1441 and 1450, Bembo painted a deck of playing cards inscribed with the emblems of both families and known today as the Visconti-Sforza tarots--the earliest extant deck to correspond card for card with the modern tarots. One of its Greater Trumps (or "triumphs") depicts a nun in a pale brown habit with a white veil and rope belt, a scepter in her right hand, a closed book in her left, and on her head, the triple tiara of the papacy (Figure 3). Although the Visconti-Sforza tarots are not labeled, this figure would be identified in subsequent decks as la Papessa.

The mysterious card was once assumed to represent the Pope Joan of medieval legend, but its iconography does not fit Joan, who had never been a nun. Rather, legend has it that she disguised herself as a man and became a learned cleric, eventually rising to the papal throne. As a cautionary gloss on the vices of women, Joan's true sex was not disclosed until she became pregnant and died in labor during a procession through the streets of Rome. (91) The Papessa of the Visconti-Sforza tarots is not Joan, therefore, but Sister Maifreda da Pirovano--an attribution first made by Gertrude Moakley in 1966, well before modern historians had rediscovered the Guglielmites. (92) Moakley's identification of the card has been widely though not universally accepted by specialists. The one sticking point has been doubt that the Visconti in 1450 would have remembered, even honored, a kinswoman whose "papal" pretensions had led to her death for heresy in 1300. But we now have further evidence that the family did just that. Beyond my suggestion that Matteo Visconti confiscated and ultimately preserved the inquisitorial record, it turns out that his last lineal heir, Bianca Maria, not only commissioned the Visconti-Sforza tarots with their remembrance of Sister Maifreda, but also brought the cult of St. Guglielma to Brunate, where an image of the "true Holy Spirit" with her martyred apostles remains to this day.

Founded by two sisters as a hermitage in 1340, the tiny church of San Andrea was a nunnery for almost three hundred years before it became a parish. But it was a very small, poor, struggling nunnery until Maddalena Albrizzi decided to enter it around 1420. (93) Albrizzi came of a distinguished family in Como, so her choice of the austere

Brunaterather than

Santa Margherita, the aristocratic Benedictine house she had first planned to enter, baffled her hagiographers. One supposed that she had been "admonished in dreams by our holy father Augustine," while another claimed that Albrizzi heard a divine voice telling her three times on the threshold of Santa Margherita to "take a different way, turn your steps to Brunate." (94) Once there she was soon elected ministra (the nuns' term for abbess), and her charismatic fervor and reformist zeal attracted enough recruits to give the convent a fresh lease on life. Albrizzi's ambitious plans for her community included the founding of a daughter house, which was needed because the lay sisters, descending to Como on begging trips, found themselves too often stranded there by storms and compelled to take shelter with hosts of dubious virtue. A daughter house in the city would insure them a safer refuge. Further, Albrizzi wished to exempt her nuns from the jurisdiction of the bishop of Como and affiliate them instead with the Augustinian Hermits. But the first of these projects required money and land, while the second required papal approval. In both of these exigencies, Albrizzi turned for help to her good friend and patroness,

Bianca Maria Visconti.

Albrizzi's life is not especially well documented, but three short vitae survive, and one of the few points emphasized by all of them is her close relationship with the duchess of Milan. The friar Paul Olmo, writing in 1484, notes that "by the authority of Popes Nicholas V and Pius II, [the nunnery at Brunate] was attached to the [Augustinian] congregation of Crema at the urgent request of Bianca Maria, duchess of Milan, who held the name of the virgin [Maddalena Albrizzi] in great reverence." (95) An anonymous vita of the late sixteenth century gives a fuller account. When Albrizzi "learned that certain nunneries in Milan had joined themselves to the Hermits of St. Augustine, an order flourishing in holiness at that time, she decided that she too would request this favor from the pope by all means. By the mediation of Bianca Visconti, who was married to the great Sforza and ruled Milan, she quickly achieved her wish." (96) Papal documents indicate that Nicholas V, in a bull of 1448, did grant the Brunate nuns' requests to follow the Augustinian rule and to construct a new monastery in Como. It was Filippo Maria Visconti who provided the quarry stones; the act of donation is dated 1443. Pius II reaffirmed the privileges of both convents at Bianca Maria's request in 1459. (97)

Other documents confirm a cordial relationship between the pope and the duchess. In 1463, for example, Pius II exhorted Bianca Maria to persuade her husband to join a crusade against the Turks, and she promised he would fight. (98) Gerolamo Borsieri, writing in 1624, had access to local documents no longer extant, which supplied further details of the friendship between Albrizzi and the duchess. As evidence of Albrizzi's modesty, he remarks that "she once asked Bianca Maria, duchess of Milan, if the revenues from certain estates bordering on her monastery might be added to the treasury. She did not allow any further mention of this matter to be made to her, although it had been easy to obtain from the princess, who used to come see her frequently." (99) Apparently Bianca Maria brought her husband with her often enough to fuel a dangerous slander. Albrizzi's detractors in Como, who resented the expansion of her community there, claimed that Francesco Sforza only used visiting the nuns at Brunate as a pretext: what really interested him was the strategic vantage point it affords over Como, since from Brunate he could easily spy out any weakness in the city's defenses with a view to conquering it. (100)

Bianca Maria's eulogies do not specifically mention Albrizzi or Brunate, but they do praise her liberality toward churches and monasteries in general. In a funeral oration for the duchess, Girolamo Crivelli asked, "Are not the churches of this city, the communities of nuns, the convents of monks, all the cities, and indeed all Italy, filled with the ample gifts of this most munificent princess?" (101) More wryly and laconically, the chronicler Filippo da Bergamo noted that Bianca Maria "built many monasteries of virgins in which she placed the illegitimate daughters of her husband." (102) We do not know whether any of Francesco Sforza's bastards became nuns at Brunate, but we do know that the monastery was expanded during Albrizzi's lifetime, and thus under Bianca Maria's patronage. At this point architectural history comes to our aid. In a letter dated October 11, 1842, Pietro Monti, then parish priest at Brunate, wrote in response to an inquiry from the historian Michele Caffi:

Monti's account of what happened in 1826 is not entirely clear: it is hard to say whether the workmen uncovered and once again whitewashed the narrative cycle of Guglielma's life, or whether they destroyed the entire wall. But it is clear enough that the lost cycle paintings, from roughly the same period, illustrated the saint's legend as Bonfadini tells it. (If they were painted in Albrizzi's lifetime, they predated Antonia Pulci's play.) In commissioning the cycle, Albrizzi added a few pious details to the legend--the hairshirt, the crucifix, the image of Mary--and made it possible to identify the convent where Guglielma had been a lay sister as Brunate itself. But we must question Pietro Monti's belief that the extant painting had once formed part of the narrative cycle. In the first place, we know that this painting had already been installed in its baroque marble frame in 1745, since the sculptor's contract happens to survive. (104) Thus the fresco had been detached from the wall that initially held it long before the whitewashed cycle paintings were disclosed to Monti. In fact, the report of Carlo Cardinal Ciceri, who paid a pastoral visit to Brunate in 1685 (thirty years after it obtained parish status), noted that the church then had three altars: a high altar, one dedicated to the Virgin, and a third to St. Guglielma. Both of the latter were adorned with paintings. (105) I would suggest that the existing fresco once decorated the chapel of St. Guglielma, but was cut out of its wall and framed when the dedication of that chapel was altered. Quite possibly it was rededicated to Maddalena Albrizzi, whose canonization the nuns of Brunate and Como had been seeking ever since her death. (106) But since Guglielma was still an object of devotion, the fresco could not be whitewashed or destroyed, but required a new and honorable setting.

The second reason to doubt Pietro Monti's assumption is that the extant painting simply does not fit any episode in Bonfadini's legend. But Monti was blissfully ignorant of the saint's heretical past, as we are not, so it is easy for us to recognize Sister Maifreda and Andrea Saramita in the two kneeling figures. If we ask how this suppressed and indeed heretical iconography could have come to Brunate, the answer should now be clear: it came from Bianca Maria Visconti. The duchess after all knew enough about Sister Maifreda to have inserted her image in the Visconti-Sforza tarots. It is also possible that the Visconti preserved an old painting of Guglielma and her devotees in a domestic chapel, such as every great family once had. We saw earlier that the Guglielmites invested heavily in liturgical art, including not only paintings but also vestments, altar frontals, and chalices, which they kept in private homes. Mirano da Garbagnate, who painted several images of St. Guglielma in Milanese churches, probably belonged to the same family as Francesco da Garbagnate, the friend and political adviser of Matteo Visconti. In addition to his public works, he could easily have created panel paintings for domestic veneration by the saint's devotees; and if he did, these would have been much easier to conceal from inquisitors. Since Mirano's cultic role within the sect was that of "special secretary" to Saramita and Maifreda, the composition with these two figures kneeling before Guglielma might well have been his. In short, if Bianca Maria had inherited such a picture, with an iconography uniquely meaningful to the sect's inner circle, the mid-fifteenth-century painting at Brunate might just conceivably derive from a late-thirteenth-century original.

Be that as it may, what we can take as near certain is that the painting was commissioned by Maddalena Albrizzi with the patronage of Bianca Maria Visconti. Thus two women of the fifteenth century, a devout princess and a spiritually ambitious nun, joined forces to revive the good fame of two other women--a devout princess and a spiritually ambitious nun--who had long ago fired their friends with hope and ardor. In this case they were joined at some distance by a third woman, Antonia Pulci, who made St. Guglielma's legend safe for public consumption and guaranteed it a diffusion far beyond the little church on the mountaintop. The path we have taken to trace Guglielma's journey from Bohemia to Milan to Brunate may seem nearly as circuitous as her story itself, yet all speculations pale before one indisputable fact. The painting, against all probability, exists--hidden in plain sight for five and a half centuries.

ACT FIVE: TOWARD THE PRESENT

From the standpoint of public piety, the establishment of Guglielma's cult at Brunate was only the beginning of her latter-day veneration. By the close of the fifteenth century, Guglielma and her new devotee, Maddalena Albrizzi, were already linked in popular imagination as the two local saints of Brunate. Although the nuns finally decamped to Como in 1593, the devotion to St. Guglielma remained. A manuscript in Como, written by the priest Giovanni Antonio da Fino, advertises the vitae of B. Maddalena Albrici e S. Guglielma del Monastero di Brunate, although only Guglielma's life (based on Bonfadini) is actually found there. (107) In 1642 a Franciscan curate of Brunate, Andrea Ferrari, republished Bonfadini's legend in modernized Italian. He gave the Hungarian king a name, Teodoro, and arbitrarily dated his marriage to Guglielma in 795. The real interest of his version lies in what it reveals about the diffusion of Guglielma's cult, for he mentions an image of her at the church of San Antonio in Morbegno, which, with delicious irony, belonged to the Dominicans. But there was also a convent of Augustinian nuns in Morbegno, so the devotion had presumably spread from Albrizzi's community, which had a significant influence on the order at large. (108) Ferrari's legend notes that people appealed to St. Guglielma to deliver them from headaches, "in sign of which she can still be seen in our days, laying hands on someone's head, in a painting." (109) Indeed, Bonfadini tells how the saint healed a ship's entire crew afflicted with that malady--a datum that could easily have lent itself to explain the iconography. The belief that a saint would cure headaches by the laying on of hands is, indeed, more obvious than the notion that she might be consecrating the first female pope in the name of the Holy Spirit! But signs of Guglielma's unconventional background persist. Not least of these is her feast day, which is, to say the least, liturgically odd. The fourth Sunday of April is the only Sunday of the year that always falls between Easter and Pentecost, but never coincides with either. No other saint has a movable feast, let alone one linked to the Easter cycle. (110) In view of the old sectarian belief that Guglielma, born on Pentecost, would rise from the dead like Jesus, the link between her thirteenth-century heretical feast on Pentecost and her modern commemoration cannot be entirely coincidental.

With the passage of time, devotion to the reinvented St. Guglielma was normalized at Brunate as she was integrated into the pantheon of saints. A baroque painting at San Andrea, executed around 1700, honors the Dominican St. Vincent Ferrer, flanked by St. Charles Borromeo on the right and a crowned St. Guglielma on the left. At some point the street leading to the church was named the "Via Santa Guglielma," and in the mid-nineteenth century a priest erected a marble plaque on the north facade of the church, honoring both Guglielma and Maddalena Albrizzi (Figure 4). It notes that "on this

mountain Santa Guglielma found shelter against the unjust wrath of her husband; here she lived and made her passage to heaven." At the turn of the twentieth century, Brunate's sudden popularity with tourists lent further publicity to its local saint. Even Sir Richard Burton, the tireless English traveler, mentions in a footnote to his Arabian Nights that "Santa Guglielma, worshipped at Brunate, works many miracles, chiefly healing aches of head." (111) But by this point the saint had gained a second healing specialty, as we learn from turn-of-the-century tourist guides. As Luigi Porlezza wrote in 1894, "many women go to the church of Brunate so that, by the intercession of Santa Guglielma, they will have enough breast milk to sustain their babies." In 1900 Zaccaria Pozzoni acknowledged, "no document exists to prove that Santa Guglielma really lived at Brunate. Yet the veneration of that saint there was and is great: how many mothers, how many wet nurses, suffering from lack of milk, still hasten there, even from far away, and ascend in devout pilgrimage to pray and make vows to her!" (112) The official Church understandably tried to turn this folk piety in the direction of moral aspiration, as we see from an indulgenced prayer published by the bishop of Como in 1912:

O glorious Santa Guglielma, in these times of great moral laxity and

weakness of character, we appeal with confidence to your

intercession to obtain strength and purity from the Divine Heart of

Jesus and his Immaculate Mother. At the school of Jesus and Mary, O

Guglielma, you studied Christian dignity and learned to respect it

in such a way that neither riches, nor honors, nor promises, nor

threats, nor privations, nor slander, nor persecution, nor exile

could ever make you unfaithful. Therefore, O Guglielma, grant that

we also may be educated at the same school of religion and virtue,

so that, with our minds healed and our hearts set free from the

thousand errors and the thousand vices of modern impiety, we may

show ourselves strong and pure, imitators of your virtue in life,

that we may be companions of your glory in the blessed homeland of

Paradise. Amen. (113)

Guglielma's story belongs to the wide realm of truths that are stranger than fiction. Princess, pinzochera, saint, divine Spirit, heretic, and saint once more, she has met the needs of her friends, disciples, persecutors, and devotees for more than seven centuries. To have set this eventful history in motion, the real Guglielma must have been a stunningly charismatic figure, yet hers is a paradoxical fate, for her strange magnetism has obscured her personality beyond all hope of recovery. It is also a peculiarly female fate, for women burned at the stake cast long and unpredictable shadows. Joan of Arc (d. 1431), the peasant girl who became a military hero to save her country, fell into the hands of her enemies who burned her for heresy, yet went on to become the patron saint of France. Marguerite Porete (d. 1310), a mystical theologianwhose courage was even more remarkable than her prose, died at the stake for her Mirror of Simple Souls, yet that very book escaped into the shelter of anonymity and found a wide, orthodox readership before finally being reunited with its author in 1946.114 Two decades earlier, Porete could have enjoyed the posthumous satisfaction of seeing her condemned book published in translation with the nihil obstat and imprimatur of the Church. (115) Like these illustrious successors, Guglielma too slipped off the yoke of heresy and returned, by the most roundabout of paths, to the sainthood her contemporaries had ascribed to her while she lived.

What makes St. Guglielma's reinvention especially remarkable is the role of the Visconti, whose rise to power under Matteo and Galeazzo coincided with her heretical cult, and whose eclipse with Bianca Maria marked her successful installation at Brunate. Others worked more publicly on Guglielma's behalf: Andrea Saramita and Sister Maifreda, those doomed enthusiasts; Maddalena Albrizzi, a kindred spirit with energy and zeal; and the fifteenth-century publicists, Antonio Bonfadini and Antonia Pulci. But without the Visconti, secretly cherishing the memory of "their" heretic saint and spreading her devotion where they could, Guglielma would have been quite forgotten, and even the record of her heretication would have been lost forever. Because of the dynasty's long defiance, however, the nuns of Brunate and, later, generations of women with throbbing heads and dry breasts would have a chance to venerate "their" saint. It is only now that the esoteric and exoteric traditions of St. Guglielma have finally converged.

If her popularity today is not what it was a century ago, its waning is due less to the labor of historians than to modern medicine, which has spelled the death of so many traditional healing cults. Not the rediscovery of a forgotten heresy, but aspirin and infant formula have stemmed the tide of pilgrims to Brunate. Yet not altogether, perhaps. On my final visit, as I was about to leave San Andrea, I encountered a gracious woman of a certain age, of the sort who is often to be seen at prayer in every

Catholic church in Europe. After some pleasantries, I pointed to the fifteenth-century painting and asked what saint that might be? Her face brightened and she said, "oh yes, that is St. Guglielma, a Hungarian princess, who was abandoned by her husband, so she came here to Brunate to live with the nuns.... And over there is Blessed Maddalena Albrizzi, their abbess.... Did you know that this church was one a convent?"